In the third part of my Chocopy Compiler Hacking series, I will be discussing how I built the backend to compile Chocopy to Microsoft’s Common Intermediate Language (CIL).

For those unfamiliar with the topic, Chocopy is a subset of Python 3 with static type annotations. CIL is the intermediate format that languages in the .NET ecosystem like C# and F# compile to, similar to how Java, Kotlin, and Scala all compile to JVM.

In this post, I’ll go over how I built on top of my work on the JVM backend, compare and contrast the two backends, and give some thoughts on JVM and CIL as compilation targets.

For reference, the source code for the compiler is available on Github, and past progress is documented on this blog. If you haven’t already, I recommend reading Part 2 before reading this, because I will make many references to the JVM backend in this blog post.

Overview #

Each time I work on this compiler I like to keep the scope manageable and have a set of well-defined goals, since my time is very limited and I dislike the idea of starting projects and never finishing.

- For the frontend and typechecker, my goal was to avoid writing my own lexer and parser by leveraging Python’s built-in parser.

- For the JVM backend, my goals were to learn more about the JVM instruction set and runtime, and to setup the foundations to easily extend the compiler with other backends.

I chose CIL as the next backend to implement because the instruction set and semantics seemed superficially similar to JVM, so I figured it would be the easiest new backend to build. I was aware of IronPython, a project that targets the .NET runtime with Python 3.4, but I intentionally chose not to reference their code.

My goals for this project were twofold: learn more about CIL as a compilation target, and reuse as much of my previous work as possible to minimize the amount of new code I had to write.

Chocopy to CIL #

The CIL backend targets a plaintext representation of CIL instructions, and uses ilasm to assemble them into executables. The Mono documentation’s description for ilasm reads as follows:

The Mono Assembler can be given disassembled text, and it creates an assembly file. This is very important, because many compilers don’t create the assembly themselves, and depend on this tool. Of course it can be also seen as a form of a compiler.

Both the plaintext representation and the assembler are standard/official parts of the toolchain, so setting up my compiler to target plaintext felt more natural and less cobbled-together. This is a big contrast with JVM, where there is no standard assembler and there are syntactical differences between the text formats accepted by different third-party assemblers.

Without going into too much detail about each feature, below is a table showing the mapping of Chocopy’s main language features into CIL. For the most part, this mapping is the same as the one from Chocopy->JVM, so please refer to that blog post for more implementation details. Although CIL is targeted by many languages, I chose C# as the main reference because it is the most similar to Java.

| Chocopy | CIL/C# |

|---|---|

| top level functions | static methods on main class |

| top level statements | body of Main function |

| classes, methods, attributes | classes, instance methods, fields |

| lists | arrays |

| nested functions | hoisted to top level/class level |

| global variables | static fields on main class |

| nonlocal variables | ref parameters |

Building on top of the JVM backend #

Compared to building out the JVM backend, building the CIL backend was much easier. My previous work on hoisting passes for nonlocals and nested functions in the JVM backend could be directly reused and the only new pass I had to write was the code generation pass for CIL.

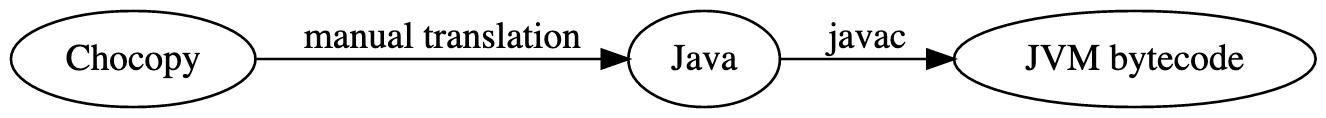

When I built the JVM code generation pass, I approached each language feature by trying to translate Chocopy programs into Java and seeing how the translated programs were compiled into JVM bytecode. Having the mental process of mapping features from Chocopy->Java->JVM was helpful for guiding the implementation process.

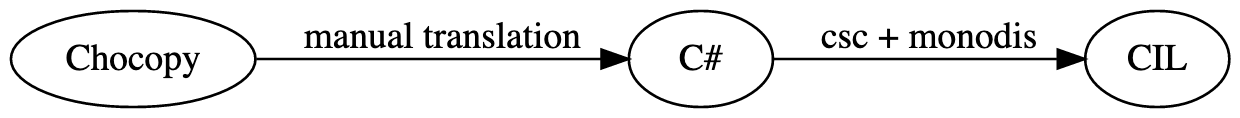

With the CIL backend I initially adopted a similar approach, by first finding a C# equivalent to Chocopy language features and seeing what CIL instructions the C# got compiled to. Although I had never written C# before, it was pretty easy to pick up enough to write some small programs.

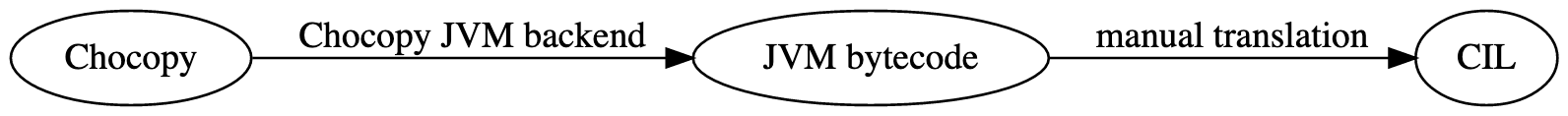

Unlike last time, I wasn’t starting from scratch, so I wanted to find a way to leverage the Chocopy->JVM mapping that I had previously developed. As it turns out, there are a lot of similarities between the JVM and CIL code structure and instruction sets, and some previous research on translating between CIL and JVM.

This meant that in addition to mapping features from Chocopy->C#->CIL, I could also approach this as a Chocopy->JVM->CIL translation task. The latter approach actually made my work a lot easier - since JVM and CIL are both relatively lower-level representations, in some cases it was very straightforward to translate between them, instead translating a higher-level language like C# or Java down to a lower-level representation.

For many parts of the CIL codegen, I just copied the JVM backend’s implementation and replaced JVM instructions and stdlib functions with their CIL equivalents. For example, using add (CIL) instead of iadd (JVM), or calling System.Console::WriteLine (CIL) instead of System.Out.println (JVM). Not every feature could be translated this cleanly, but in places when this was possible I saved a lot of time.

Local Variables #

Most of the differences between the CIL and JVM backends were minor, but one big aspect where they differ is the handling of local variables.

Functions in CIL are required to declare the stack positions, names, and types of every local variable in a .locals block. To my understanding, local variables cannot be dynamically created outside of that block and the stack cannot be randomly accessed unless the position is declared in the locals block. These locals included not just user-defined variables, but also generated variables used in for-loops and string/list concatenation.

In the JVM backend this wasn’t a requirement, so I was able to store and load anything from arbitrary positions on the stack without declaring them beforehand. Additionally, the JVM instruction set supported an extensive set of stack operations, so in many cases I didn’t need to store temporary values lower in the stack and simply used operations like dup2 or swap to reorder values to my liking.

For example, take the assignment operation, which requires the right hand expression to be computed first to support multiple assignment. In the JVM backend, the generated code would look something like this pseudo-code:

<compute value>

load <array> // stack is [..., value, array]

swap // stack is [..., array, value]

load <index>

swap // stack is [..., array, index, value]

aastore

The CIL instruction set does not support many stack operations; outside of loading and storing locals, the stack can be modified only by adding and removing values from the top. This means that the generated CIL code would look something like this pseudo-code:

<compute value>

store <new_temp_local>

load <array>

load <index>

load <new_temp_local>

stelem

Operators - Added 6/2023 #

Unlike JVM, CIL doesn’t have a standard library function that matches Python’s modulo implementation. Again, the rem instruction does not match.

Instead, we have to implement it as follows: ((a % b) + b) % b)

Similarly to the JVM backend, we implement the short-circuiting operators as ternaries.

Debugging and Testing #

Since the assembler does not validate correctness or semantics, debugging the generated code is mostly manual. I used a combination of Mono’s command line tools (csc, ilasm, monodis) and an online C# compiler/decompiler to debug the generated CIL code.

Decompilers in particular are super useful for debugging, because they make errors in the generated instructions much easier to spot. If a generated CIL module fails at runtime, my first step would always be to disassemble it into C# - oftentimes the resulting C# code would have strange artifacts and fail to typecheck, which were excellent indicators of 1. what caused the program to fail and 2. what part of the compiler should be fixed.

Allow me to demonstrate with a specific example. Here is a cryptic error message printed when a generated CIL program failed to execute:

[ERROR] FATAL UNHANDLED EXCEPTION: System.InvalidProgramException: Invalid IL code in test:myfunction (long[]): IL_0024: stelem 0x1b000001

Putting the generated code into the decompiler yielded a C# program with this suspicious-looking code:

long[] array = new long[1];

array[0] = 1L;

long num = ((long[])array[0])[0];

It was easy to spot that the array was being indexed an extra time. In the corresponding section of CIL code, I found that these instructions were duplicated:

ldc.i4.0

ldelem i8

ldc.i4.0

ldelem i8

Just two extra instructions buried in hundreds or thousands of instructions - very challenging to spot with my untrained eye.

After removing the duplicate codegen, the test program was able to execute successfully and the decompiler output looked correct as well:

long[] array = new long[1];

array[0] = 1L;

long num = array[0];

JVM vs CIL #

I want to take some time to discuss the differences I observed between CIL and JVM as compilation targets. I won’t dive into specifics about type erasure or memory layouts since I didn’t have to deal with those for this project, so this discussion is probably most relevant for compiling high-level object-oriented languages.

Primitives and Value Types #

I prefer the way CIL handles value types and primitives compared to JVM. JVM bytecode has a lot of Java-specific design decisions baked into the instruction set and semantics, which results in weird limitations that have to be worked around.

In JVM, the primitive value types are not part of the same type hierarchy as classes. There exists a set of wrapper classes corresponding to each primitive which do belong to the class hierarchy, and values need to be wrapped or unwrapped depending on how they are being used. The Java compiler does this wrapping automatically in some situations through a feature called autoboxing, and any compiler targeting JVM would likely have to implement autoboxing as well.

It’s worth nothing that even with autoboxing, JVM does not allow passing around mutable references to primitives, because the wrapper classes are immutable. In order to simulate refs, values need to be explicitly wrapped in an array or some wrapper class, which is very inefficient (this is how I implemented nonlocals for the JVM backend).

In CIL, numeric and boolean types are part of the same type hierarchy as other data types and are subtypes of Object. References to variables or fields containing primitives can be passed around just like any other references, so there was no need for the wrapper class workaround when I implemented the CIL backend.

Instruction Set #

The JVM instruction set has a much richer set of stack operations, supporting instructions like dup2, swap, etc. that CIL does not support.

On the other hand, CIL has instructions that perform arithmetic with overflow checking, which is something entirely missing from the JVM instruction set (JVM’s integer operations silently overflow/underflow).

Another thing to note is that CIL’s instructions are mostly generic: the add instruction works on multiple numeric data types, whereas JVM has different flavors (iadd, dadd, fadd, ladd) for different data types. This didn’t make a huge difference while I was implementing the compiler, but instruction selection should be quite a bit simpler with CIL compared to JVM.

Assembler #

CIL has an officially supported text representation and an officially supported assembler. This makes it easy to target CIL without dealing with binary representations.

The same is not true for JVM. ALthough Java has an officially supported disassembler which outputs bytecode in a human-readable text format, for unknown reasons there is no official tool to do the opposite. Anyone looking to compile to JVM would have to target the binary representation, or use a third-party assembler like I did. Third party assemblers have their own problems - sometimes they’re poorly documented or unmaintained, and the supported syntax between different assemblers can be slightly different.

Conclusion #

Overall, I felt that this project was generally successful in meeting the goals I had set out. I learned a lot about CIL, C#, and the .NET ecosystem, and I gained some insights into how CIL compares to JVM. Writing the CIL backend was remarkably simple, I did it over approximately 2 days and only had to write around 700 lines of code. CIL is a pretty high level compilation target and it was very similar to JVM, which made things quite a bit simpler for me.

For future work, I’d like to explore targeting some lower level languages with this compiler, like WASM or LLVM. Targeting those will likely be harder than JVM/CIL, since they require manual memory management and don’t have high-level object-oriented concepts like classes/fields/methods baked into the language. Of course, if anyone reading this has any suggestions for what I could try next, I’d be happy to hear them.